artists we hate to love

A new memoir questions great art made by flawed men

Words by B.L. Crook

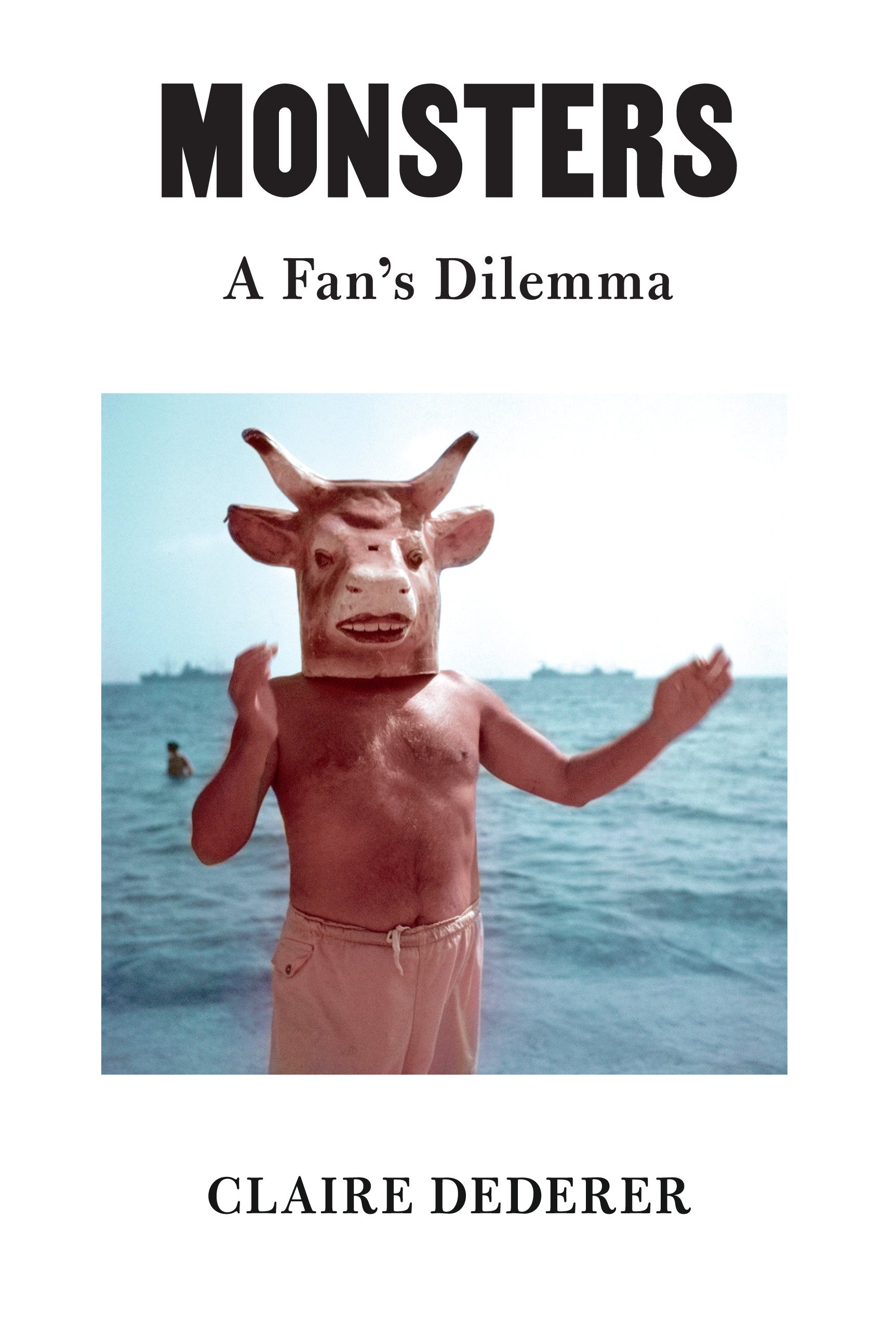

Photo: Stanton J. Stephens

I like to assume I’m not the only working-mother-artist who has forwarded Claire Dederer’s 2017 Paris Review essay “What Do We Do With the Art of Monstrous Men?” to all their mom friends. Perched on the toilet in my locked bathroom (my mid-pandemic refuge from motherhood, homeschooling and Zoom), I forwarded it to my group of island writer friends. They all replied with thumbs-ups and !! from their toilets. Not only did the article examine our inconvenient feelings about beloved art by badly behaved men, it also pointed out how frequently women artists get labeled as monstrous by doing nothing more nefarious than neglecting the kids in order to create.

That essay is now part of Claire Dederer’s latest memoir, Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma, to be published April 25 by Knopf. I met her one winter morning in Seattle to discuss her book. A long-time Bainbridge Island resident, Dederer recently moved into her late father’s historic Seattle houseboat. Bundled in pink ski clothes, Dederer tells me The Paris Review article felt like a new way of questioning the transgressive behavior of prominent men. When she started writing it in 2016, in the pre-#MeToo era, she couldn’t find much written on the topic. The idea stemmed from writing her previous book, Love and Trouble.

“For that book, I researched my favorite filmmaker, Roman Polanski. I probably learned more than most about the terrible things Polanski’s done.” (He pleaded guilty to raping a 13-year-old girl). “But after that book was published, I found I still loved watching his movies. I still loved Chinatown and Rosemary’s Baby, in spite of everything. How can this be?”

That insistent, questioning voice—how can this be?— drives the arc of Monsters, probing ever deeper. Can the work of monstrous men be objectively or aesthetically good? Who gets to say? What’s my responsibility as the audience/fan/consumer? What if I love the art? What about empathy for the wrongdoer?

Am I myself a monster? Am I monster enough to be deemed a true artist?

Dederer follows the rabbit holes of several sharp critiques—feminist, capitalist, cancel-culture—intentionally never settling on any single perspective as authoritative, yet squarely acknowledging that an artist and their work is only half of the equation. We, the audience members, are the other half. What we bring to the experience of the art is, in part, precisely why we love it so much. In spite of everything. Understanding why we love monstrous art, monstrous men, monstrous artists, monstrous people, our own monstrous selves, is as much an exercise in self-awareness as it is a critical epiphany.

I ask Dederer if revealing some hard truths about herself in the book made her uncomfortable. Yes, she admits, but as a memoirist she finds this easier than having to figure out what she thinks.

Developing a stance on cancel culture in the book, for instance, was much more frightening than being candid about her own vices.

How has her idea of the “monstrosity” of female/mother artists shifted? Dederer replies by recalling the non-gendered, tentacled monster called “Aunt Beast” from the novel A Wrinkle in Time. “Meg is whisked away in a particularly intense and dark moment to be nurtured, renewed. We need to reinvent the problem of selfishness and guilt,” Dederer says. “We need to redefine it as self-ness;” as something essential for creativity and love.

I believe Monsters is, ultimately, a love story. About the art that moves us, about the sheer necessity of being moved, in all the complexity of what that means, about the reckoning with our own demons that changes how we see others, and most of all, about that mysterious urge to love, in spite of everything.

Catch Dederer discussing Monsters on May 16 at 6:30 p.m. at Eagle Harbor Books on Bainbridge Island. RSVP here.

One of the most anticipated books of 2023, according to Kirkus Reviews and Eagle Harbor Books