kingdom of kelp

Can tending kelp gardens restore a keystone species to the Salish Sea?

Words by Ben Doerr

Photos by Kelsey Bernert

Under calm but moody skies last March, I departed Eagle Harbor in my runabout on a scientific mission. Two volunteer divers and I sped off toward a dock in Manchester, where we were greeted by lab and field teams from Puget Sound Restoration Fund (PSRF). The Bainbridge Island-based nonprofit had enlisted us and a dozen or so other volunteers as citizen scientists in its latest efforts to restore once-abundant bull kelp to Puget Sound.

At the dock, we collected and prepared our supplies, including bull kelp in its earliest stage of life, then departed once again, this time directly for Blakely Rock. This is one of several sites around Bainbridge Island that PSRF has selected for a new volunteer-led, kelp gardening initiative. Once at Blakely Rock, the divers rolled off the sides of my boat, dove below and began wrapping parts of the rocky reef with twine coated in kelp seed. The occasion felt momentous.

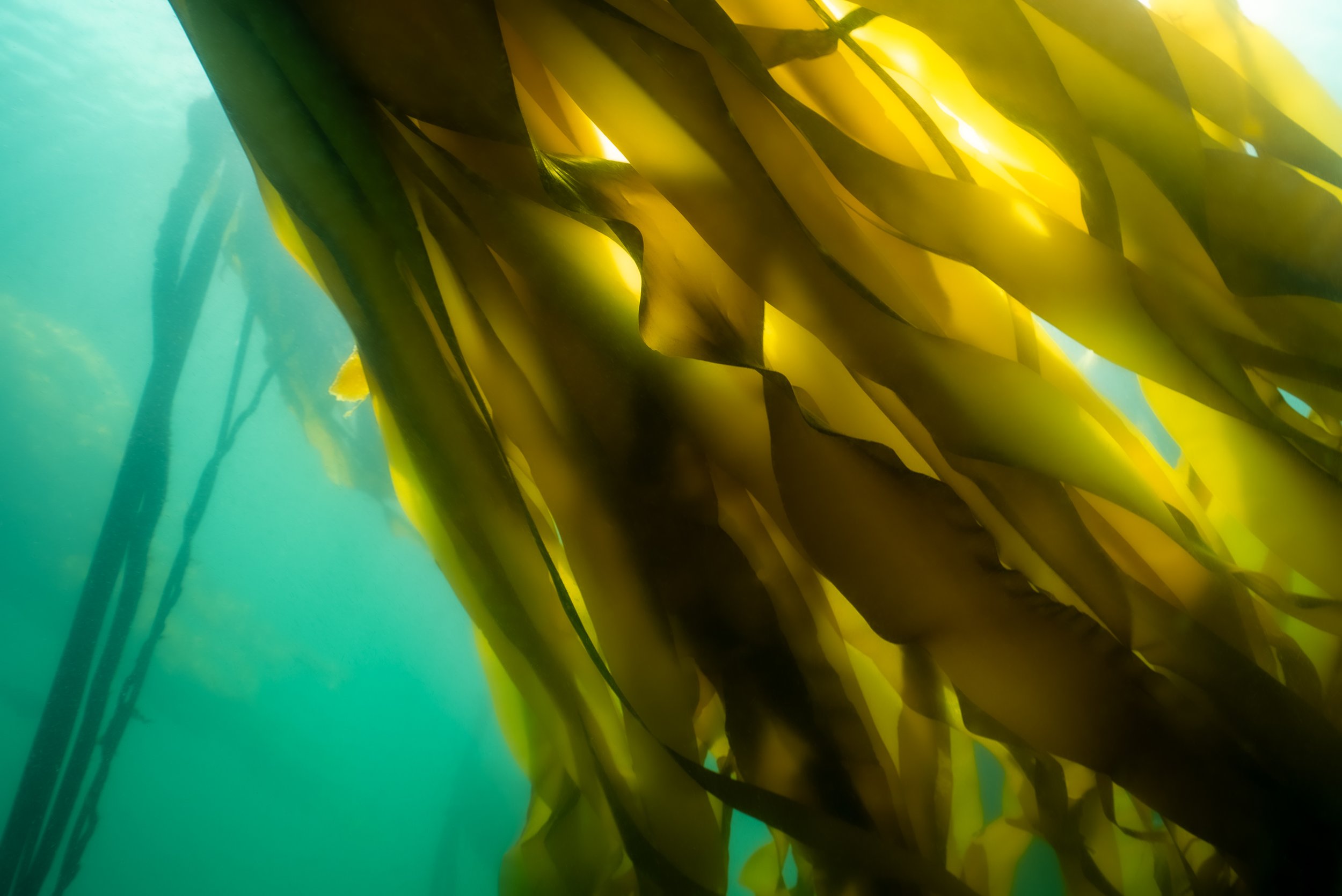

In my decade of running a sailing charter business on Bainbridge Island, I’ve amassed countless hours moving through our local waters and observing changes—seasonal, long-term and potentially harmful ones. When I moved to the island 15 years ago, bull kelp (named for its bullwhip-like appearance) was already in serious decline, and since then I’ve seen it nearly disappear from our shoreline. Most noticeable to me is the north side of Blakely Rock, which once had a relatively large kelp bed. I don’t know when it completely disappeared from there, but it has undeniably vanished, taking its slow, choreographed dance in the current and swell with it.

Missing its beauty and the way the light moves through the leaf-like blades, I started to percolate on an idea. I wanted to be involved in a legacy of improvement while putting my underutilized degree in ecology and conservation to use. I wanted to be a part of something that leaves this magical place better than I found it. Surely someone was already working on great ideas and I could just “get in where I fit in.” All roads pointed to PSRF, an organization committed to the local restoration of bull kelp and ecological conservation of our waterways.

I reached out to its founder, Betsy Peabody, in late 2023, and my timing couldn’t have been better. The organization was just launching a brand new, citizen science initiative to explore a new approach to seeding bull kelp—an annual—in a restorative effort that is low-cost, has potential to be far reaching and scalable, and requires minimal infrastructure. They call it kelp gardening. Brilliant.

At its simplest, kelp gardening is “out-planting” or “seeding” bull kelp at chosen restoration sites with minimum impact and little to no infrastructure. It’s not exactly planting or seeding since we start with gametophytes, which are multicellular organisms in an early phase of the algae life cycle. Think embryos, but for plants.

And this is where it gets cool. PSRF develops bull kelp gametophytes in their lab from local kelp beds. This gametophyte material, suspended in water, can then be mixed into a sodium alginate (a substance with the consistency of hair gel) and essentially painted onto dry rocks or natural fiber twine. Once the alginate dries, the material can be placed into salt water. “Seeded” rocks can be placed on location, and kelp-painted twine can be wrapped around existing underwater substrate, such as rocks and pilings.

This technique, using biodegradable twine, has been used for some time in kelp aquaculture. The kelp twine is often wrapped onto large scale infrastructure involving anchors and floats with heavy line run between them in rows, creating a floating farm. This is a beautiful thing, and kelp aquaculture continues to show wonderful benefits for our waters (see sidebar below).

To bring kelp back to its historic habitat in a more low-tech, low-impact way, PSRF enlisted community members as volunteer kelp gardeners last year at three sites along the shallows of Bainbridge Island’s shoreline, which are accessible by paddleboard or snorkeling. A fourth site, Blakely Rock, is near and dear to my heart and a deeply dynamic location that’s harder to reach. Its visible appearance, shape and accessibility change with the tides. At negative tides, the rock shows its long shell beach to the west and its wonderful tidepools on the north side. Crabs, sea stars, seals, birds, seaweeds and kelps are diverse and plentiful there. However, the absence of bull kelp, historically present and thriving, is notable. Given that I had a boat to access the rock and diver friends who would readily volunteer, I stepped up to oversee the site.

One truth I’ve long understood is that science rarely moves quickly or in a linear fashion, especially in the trial-and-error world of conservation and restoration. None of the four pilot sites reported kelp growth last year. Undeterred, PSRF is gearing up for another season of kelp gardening this spring and refining its methods. Kelp restoration is a long game, Peabody maintains. And lessons are being learned and shared up and down the West Coast and across the globe, including in Australia, where scientists are trying to regrow giant kelp forests with similar methods. “We did not grow kelp last year, but we had an incredible response from the community,” Peabody said. “We set the stage, saying we’re going to figure this out together.”

So we begin again, returning this year to Blakely Rock, Agate Pass and Rich Passage while adding a fifth site at Restoration Point. PSRF will make a number of adjustments from the lab to the field, such as increasing the density and quantity of kelp seed, growing it longer in the lab and planting it at a later life stage. That’s what I love about this project—it has been a magnificent learning experience for everyone involved.

The big question of course is, what caused the decline of kelp? Is it a rise in water temperature? Pollution? Habitat destruction? This is the million dollar question—and it must be followed by: How can we help restore it with minimal collateral impact?

I feel deeply grateful to be one of Peabody’s “intrepid, early-stage, kelp gardeners.” It’s the feeling I’ve been seeking for some time—being part of something that is beyond ourselves, beyond our productivity and our efficiency and earning potential. I’m part of something that may take longer than my own lifetime to sort out, but something I’d gladly offer that lifetime in service of.

Did you know?

Kelp forests absorb more carbon through photosynthesis than our native temperate rainforests. The large brown macroalgae species known as bull kelp captures this carbon as it grows an astounding 20 inches per day. All of this culminates in a large, canopy-forming plant that occupies relatively shallow waters. It protects against shoreline erosion, provides shelter for numerous creatures and serves as a food source—even after it dies.

Also known as Nereocystis luetkeana (Greek for ‘mermaid’s bladder’), bull kelp plays an important role upland in the fields and forests. Many fish, including salmon and herring, carry a large percentage of the carbon from kelp they absorb through the food chain. When an animal, such as an eagle, eats a fish and leaves both the carcass and its droppings in the forest, nutrients from the kelp are absorbed into the upland ecosystem.

Kelp Farming

Mike Spranger and Gretchen Aro own Pacific Sea Farms on Vashon Island. The couple installed the sugar kelp farm in Colvos Passage off the island’s southwest shore last November after a multi-year planning and permitting process. Spranger explains that “seaweed, and specifically the sugar kelp we grow, tastes great and is a very healthy food source. In addition, it’s great for the marine environment.”

Most people in the Pacific Northwest are unfamiliar with seaweed farms, which are just getting off the ground (er, sea floor) here. From the surface, they see unassuming lines of buoys because the majority of the farm is underwater. There are no nets involved, just anchors, lines, buoys and some hardware to connect it all together.

Spranger spends a lot of time tending to the family-run farm. “I’m on the water four to five times a week,” he notes. “It’s about a 15-minute commute by boat to the farm. I check to make sure all the lines are secure and that no debris has gotten tangled. Some days it’s a 10-minute effort and on other days it’s four hours in the rain fixing things. But both of those kinds of days are good.”

“I get calls and emails daily from people who want to get involved somehow or simply just learn more. There is something about seaweed and seaweed farming that inspires people.” / Richard Rosenthal